Last time on Samposium, I gave a more detailed look at the project I’m working on and an overview of what has been done so far. We have 870 lanelets to pre-process and improve into samples. In this post, I explain how the project has turned into a dangerous construction site.

While trying to anticipate expected work to be done in a previous post, I wrote:

I also recall having some major trouble with needing to re-align the failed samples to a different reference: these samples having failed, were not subjected to all the processing of their QC approved counterparts, which we’ll need to apply ourselves manually, presumably painstakingly.

‘Painstakingly’ could probably be described as an understatement now. For the past few weeks I’ve spent most of my time overseeing the construction of bridges.

Bridgebuilding

References

Pretty much one of the first stops for genomic data spewed out of the instruments here is an alignment to a known human reference. It’s this step that allows most of our downstream analysis to happen, we can “pileup” sequenced reads where they belong along the human genome, compare them to each-other or other samples and attempt to make inferences about where variation lies and what its effects may be.

Without a reference — like the metagenomic work I do back in Aberystwyth — one has to turn to more complicated de novo assembly methods and look for how the reads themselves overlap and line up in respect to eachother rather than a reference.

Releases of the “canonical” human reference genome are managed by the Genome Reference Consortium, of which the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute is a member. The GRC released GRCh37 in March 2009, seemingly also known as hg19. It is to this reference that our data was aligned to. However, to combat some perceived issues with GRCh37, the 1000 Genomes Project team constructed their own derivative reference: hs37d5.

To improve accuracy and reduce mis-alignment, hs37d5 includes additional subsequences termed “decoy sequences”. These decoys prevent reads whose true origin is not adequately represented in the reference from mapping to an arbitrarily similar looking location somewhere else in the genome. Sequences of potential bacterial or viral contaminants, such as Epstein-Barr virus which is used in immortalisation of some types of cell line are also included to prevent contaminated reads incorrectly aligning to the human genome.

The benefits are obvious, fewer false positives and more mapped sequence for the cost of a re-alignment? Understandably, our study decided to remap all good lanelets from GRCh37 to hs37d5 and re-run the sample improvement process.

Recipe

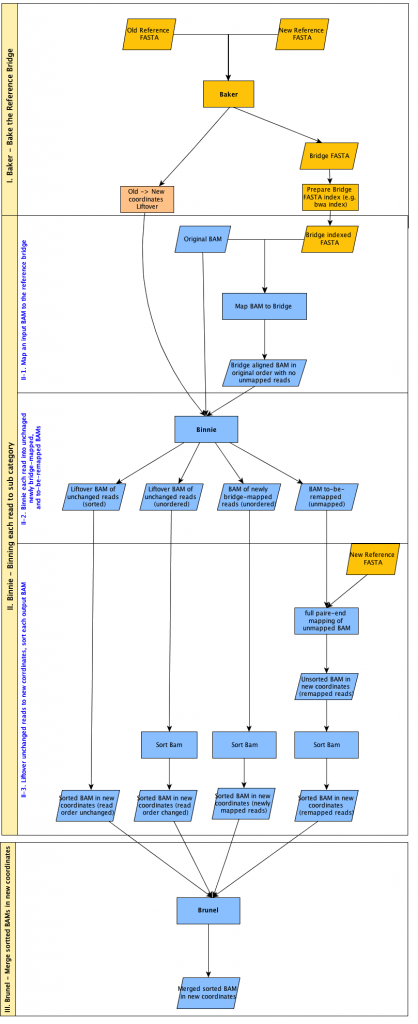

Of course, to execute our quality control pipeline fairly, we too must remap all of our lanelets to hs37d5. Luckily, Josh and his team had already conuured some software to solve this problem in the form of bridgebuilder whose components and workflow are modelled in the diagram below:

bridgebuilder has three main components summarised thus:

- baker

Responsible for the generation of the “reference bridge”, mapping the old reference to the new reference. In our case, the actualGRCh37reference itself is bridged tohs37d5. The result is metaphorically a collection of bridges representing parts ofGRCh37and their new destination somewhere inhs37d5. - binnie

Takes the original lanelet as aligned to the old reference and using thebaker‘s reference bridge works out whether reads can stay where they are, or whether they fall in genomic regions covered by a bridge. For each of the 870 lanelets, the result is the population of three bins:

— Unbridged reads

Reads whose location inhs37d5is the same as inGRCh37and do not require re-mapping.

— Bridged reads

Reads that do fall on a bridge and are mapped across fromGRCh37tohs37d5.

— Unmapped reads that are now mapped

Reads that did not have an alignment toGRCh37but now align tohs37d5. - brunel

Takes thebinniebins as “blueprints” and merges all reads to generate the new lanelet.

Whilst designed to function together and co-existing in the same package, bridgebuilder is not currently a push button and acquire bridges process. Luckily for me, back in 2014 while I was frantically finishing the write-up of my undergraduate thesis, Josh had quickly prepared a prototype Makefile with the purpose of orchestrating our construction project.

This was neat, as it accepted a file of filenames (a “fofn”) and automatically took care of each step and all of the many intermediate files inbetween. More importantly it provided a wrapper for handling submission of jobs to the compute cluster (the “farm”). The latter was especially great news for me, having spent most of my first year battling our job management system back in Aberystwyth.

In theory remapping all 870 lanelets should have been accomplished through one simple submission of Make to the farm. As you may have guessed by my tone, this was not the case.

Ruins

Shortly before calling it a day back in 2014, Josh gave the orchestrating Makefile a few shots. The results were hit and miss, a majority of the required files failed to generate and the “superlog” containing over a million lines aggregated stdout from each of the submitted jobs was a monolithic mish-mash of unnavigable segmentation faults, samtools errors, debugging and scheduling information. Repeated application of the Makefile superjob yielded a handful more desired files and the errors appeared to tail off, yet we were still missing several hundred of the final lanelets. Diagnosing where the errors were arising was particular problematic due to two assumptions in the albeit rushed design of our Makefile:

- Error Handling

TheMakefiledid not expect to have to handle the potential for error between one step and the next. Many but by no means all of the errors pumped to the superlog pertained to the absence of intermediate files, rather than a problem with execution of the commands themselves. - Error Tracing

There was no convenient mechanism to trace back entries from the superlog to the actual cluster job (and thus particular lanelet) to try and reproduce and investigate errors. The superlog was just a means of establishing a heartbeat on the superjob and to roughly guage progress.

This is where the project left off and to where we must now return.

Revisiting Wreckage

As expected, given nothing had been messed around with in the project’s year long hiatus, rebooting the bridgebuilding pipeline via the Makefile provided similar results as before: some extra files and a heap of errors of unknown job origin. However, given there was non-trivial set of files that the pipeline marked as complete, there were less files to process overall and so many less jobs were submitted as a result, thus inspecting the superlog was somewhat easier.

I figured a reasonable starting point would be to see whether errors could be narrowed down by looking for cluster jobs that exited with a failed status code. Unfortunately the superlog doesn’t contain the LSF summary output for any of the spawned jobs and so I had to try and recover this myself. I pulled out job numbers with grep and cut and fed them to an LSF command that returns status information for completed jobs. I noticed a pattern and with a little grep-fu I was able to pull-out jobs that failed specifically due to resource constraints, a familiar problem. Though in this case, the resource constraints were imposed on each job by rules in the Makefile, the cure was to merely be less frugal.

Generously doubling or tripling the requested RAM for each job step and launching the bridgebuilder pipeline created an explosion of work on the cluster and within hours we had apparently falled in to a scenario where we had a majority of the files desired.

But wielding a strong distrust for anything that a computer does, I was not satisfied with the progress.

Reaping with quickcheck

Pretty much all of the intermediary files, as well as the final output files are “BAMs”. BAM (Binary sAM) files are compressed binary representations of SAM files that contain data pertaining to DNA sequences and alignments thereof. samtools is a suite of bioinformatics tools primarily designed to work with such files. After anticipated of samtools index proved unreliable for catching more subtle errors, Josh wrote a new subcommand for samtools called: quickcheck.

samtools quickcheck is capable of quickly checking (shocker) whether a BAM, SAM or CRAM file appears “intact”; i.e. the header is valid, the file contains at least one target sequence and for BAMs that the compressed end-of-file (EOF) block is present, which is elsewise a pretty good sign your BAM is truncated. I fed each of the now thousands of BAM files to quickcheck and hundreds of filenames began to flow up the terminal, revealing a new problem with the bridgebuilder pipeline’s Makefile:

- File Creation is Success

The existence of a file, be it an intermediate or final output file is viewed as a success, regardless of the exit status of the job that created that file.

The Makefile was set-up to remove files that are left broken or unfinished if a job fails, but this does not happen if the job is forcibly terminated by LSF for exceeding its time or memory allocation, which was unfortunately the case for hundreds of jobs. This rule also does not cover cases where a failure occurs but the command does not return a failing exit code, a problem that still plagues older parts of samtools. Thus, quickchecking the results is the only assuring step that can be performed.

Worse still, once a file existed, the next step was executed under the assumption the input intermediate file must be valid as it had not been cleaned away. Yet this step would likely fail itself due to the invalid input, it too leaving behind an invalid output file to go on to the next step, and so on.

As an inexpensive operation, it was simple to run quickcheck on every BAM file in a reasonable amount of time. Any file that failed a quickcheck was removed from the directory, forcing it to be regenerated anew on the next iteration of the carousel pipeline.

Rinse and Repeat

After going full-nuclear on files that upset quickcheck, the next iteration of the pipeline took much longer, but thankfully the superlog was quieter with respect to errors. It seemed that having increased limits on the requests for time and memory, most of the jobs were happy to go about their business successfully.

But why repeat what should be a deterministic process?

- Jobs and nodes fail stochastically

We’re running a significant number of simultaneous jobs, all reading and writing large files to the same directory. It’s just a statistical question of when rather than if at least one bit goes awry, and indeed it clearly does. Repeating the process and removing any files that failquickcheckallows us to ensure we’re only running the jobs where something has gone wrong. - The

Makefilestalls

Submitting aMakefileto a node with the intention for it to then submit jobs of its own to other nodes and keep a line of communication with each of them open, is potentially not ideal. Occasionally server blips would cause these comm lines to fail and theMakefilewould stall waiting to hear back from its children. In this scenario the superjob would have to be killed which can leave quite a mess behind.

Following a few rounds of repeated application of the pipeline and rinsing with quickcheck, we once again appeared in the reasonable position of having the finish line in sight. We were just around 200 lanelets off our 870 total. A handful of errors implied that some jobs wanted even more resources and due to the less monolithic nature of the superlog, a repetitive error with the final brunel step throwing a segmentation fault came to my attention.

But not being easily satisfied, I set out to find something wrong with our latest fresh batch of bridges.

Clobbering with sort

After killing a set of intermediary jobs that appeared to have stalled — all sorting operations using samtools sort — I inspected the damage; unsurprisingly there were several invalid output file, but upon inspection of the assigned temporary directory, only a handful of files named .tmp.NNNN.bam (where NNNN is some sequential index). That’s odd… There should have been a whole host of temporary files…

I checked the Makefile, we were using samtools sort‘s -T argument to provide a path to the temporary directory. Except -T is not supposed to be a directory path:

|

1 2 |

-T PREFIX Write temporary files to PREFIX.nnnn.bam |

So, providing a directory path to -T sets the PREFIX to \path\to\tmp\.NNNN.bam.

Oh shit. Each job shared the same -T and must therefore have shared a PREFIX, this is very bad. Immediately I knocked up a quick test case on my laptop to see whether a hunch would prove correct, it did: I found a “bug” in samtools sort: samtools sort clobbers temporary files if “misusing” -T.

Although this was caused by our mistaken use of -T as a path to a temporary directory not a “prefix”, the resulting behaviour is dangerous, rather unexpected and as explained in my bug report below, woefully beautiful:

Reproduce

Execute two sorts providing a duplicate prefix or duplicate directory path to

-T:Result

output1.sam contains input2.sam’s header along with read groups appearing in input2.sam and potentially some from input1.sam. output2.sam is not created as the job aborts.

Behaviour

- Job A begins executing, creating temporary files in tmp/ with the name

.0000.tmpto.NNNN.tmp.- Job B begins, chasing Job A, clobbering temporary files in tmp/ from

.0000.tmpto.MMMM.tmp.- Job A completes sorting temporary files and merges

.0000.tmpto.NNNN.tmp. Thus incorrectly including read groups from Job B in place of the desired read groups from Job A, where N <= M.- Job A completes merging and deletes temporary files.

- Job B crashes attempting to read

.0000.tmpas it no longer exists.

By default, samtools sort starts writing temporary files to disk if it exceeds 768MB of RAM in a sorting thread. Initially, none of the sorting jobs performed by the Makefile were alloted more than 512MB of RAM total and thus any job on track to exceed 768MB RAM should have been killed by LSF and a temporary file would never have touched disk. When I showed up and liberally applied RAM to the affected area, sorting operations with a need for temporary files became possible and the clobbering occurred, detected only by luck.

What’s elegantly disconcerting about this bug is that the resulting file is valid and thus cannot be identified by quickcheck, my only weapon against bad BAMs. A solution would be to extract the header and every readgroup that occurs in the file and look for at least one contradiction. However, due to the size of these BAMs (upwards of 5GB, containing tens of millions of alignment records) it turned out to be faster to regenerate them all, rather than trying to diagnose which specifically might have fallen prey to the bug for targeted regneration.

I altered the Makefile to use the name of the input file after the path when creating the PREFIX to use for temporary files in future, side-stepping the clobbering (and using -T as intended).

brunel and The 33

Following the regeneration of any sorted file (and all files that use those sorted files thereafter), it was time to tackle the mysterious stack of segementation faults occuring at the final hurdle of the process, brunel. Our now rather uncluttered superlog made finding cases for reproducing simple, especially given the obvious thirty eight line backtrace and memory map spewed out after brunel encountered an abort:

|

1 2 3 4 |

*** glibc detected *** /software/hgi/pkglocal/bridgebuilder-0.3.6/bin/brunel: munmap_chunk(): invalid pointer: 0x00000000022ec900 *** [...] /tmp/1436571537.7566550: line 8: 21818 Aborted /software/hgi/pkglocal/bridgebuilder-0.3.6/bin/brunel 8328_1#15.GRCh37-hs37d5_bb_bam_header.txt 8328_1#15_GRCh37-hs37d5_unchanged.bam:GRCh37-hs37d5.trans.txt 8328_1#15_GRCh37-hs37d5_remap.queryname_sort.map_hs37d5.fixmate.coordinate_sort.bam 8328_1#15_GRCh37-hs37d5_bridged.queryname_sort.fixmate.coordinate_sort.bam 8328_1#15.GRCh37-hs37d5_bb.bam |

Back with our old friend, gdb, I found the error seemed to occur when brunel attempted to free a pointer to what should have been a line of text from one of the input files:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

char* linepointer = NULL; [...] while (!feof(trans_file) && !ferror(trans_file) && counter > 0) { getline(&linepointer, &read, trans_file); [...] } free(linepointer); |

Yet if linepointer was never assigned to, perhaps because trans_file was empty, brunel would attempt to free NULL and everything would catch fire and abort, case closed. However whilst this could happen, my theory was disproved with some good old-fashion print statement debugging — trans_file was indeed not empty and linepointer was in fact being used.

After much head-scratching, more print-debugging and commenting out various lines, I discovered all ran well if I removed the line that updates the i-th element of the translation array, trans. How strange? I debugged some more and uncovered a bug in brunel:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 |

int *trans = malloc(sizeof(int)*file_entries); char* linepointer = NULL; [...] while (!feof(trans_file) && !ferror(trans_file) && counter > 0) { getline(&linepointer, &read, trans_file); [...] // lookup tid of original and replacement int i = 0; for ( ; i < file_entries; i++ ) { char* item = file_header->target_name[i]; if (!strcmp(item,linepointer)) { break; } } int j = 0; for ( ; j < replace_entries; j++ ) { char* item = replace_header->target_name[j]; if (!strcmp(item,sep)) { break; } } trans[i] = j; counter--; } free(linepointer); |

Look closely. Assignments to the trans array rely on setting both i and j by breaking those two loops when a condition is met. However if the condition is never met, the loop counter will be equal to the loop end condition. This is particularly important for i, as it is used to index trans.

At a length of file_entries, assigning an element at the maximum bound of loop counter i: file_entries, causes brunel to write to memory beyond that which was allocated to the storing of trans, likely in to the variable that was assigned immediately afterwards… linepointer.

So it seems that linepointer is not NULLbut is infact mangled with the value of file_entries. I added a quick patch that checked whether i < file_entries before trying to update the trans array and all was well.

Yet, curiosity got the better of me, only a small subset (33/870) files were throwing an abort at this brunel step, why not all of them? What’s more, after some grepping over our old pipeline logs, the same 33 lanelets each time too. Weird.

Clearly they all shared some property. The lanelet inputs were definitely valid and a brief manual inspection of the headers and scroll through the body showed nothing glaringly out of place. Focussing back on the function of brunel and the nature of this error: the i loop not encountering a break because the exit condition is not met, gives us a good place to start.

These loops in brunel are designed to “translate” the sequence identifiers from the old reference, to that of the new reference. For example: the label for the first chromosome in GRCh37 is “Chr1” but in hs37d5, it’s known simply as “1”. It’s obviously important these match up and ensuring that is in the purpose of the build_translation_file function. This mapping is defined by a text file that is also passed to brunel at invocation. If there is a valid mapping to be made, the loops meet their conditions and when trans[i] = j: i refers to the SQ line in the header to be translated and j refers to the new SQ line in the new file that will contain all the reads. Lovely.

What about when there are no valid mappings to be made? Under what conditions could this even happen? The i-loop would never meet its break condition if a chromosome to be translated (as listed in the translation text file) was never seen in the first place. i.e. There were no sequence identifiers using the GRCh37 syntax. A sprinkling of debugging print statements confirmed no translations ever occurred, and trans[i] = file_entries was always the result for each iteration through the translation file…

I opened the headers for one of “the 33” lanelets again and confusingly, it was already mapped to hs37d5.

Turns out, these 33 lanelets were from a later phase of the study from which they originated and thus had already been mapped to hs37d5 as part of that phase’s pipeline. We’d been trying to forcibly remap them to the same reference they were already mapped to.

The solution was simple, remove the lanelet identifiers for “the 33” from our pipeline and pull the raw lanelets (as they’ve already been mapped to hs37d5) from the database later. We now had just 837 lanelets to care for.

The 177

That should have been the end of things, the 837 lanelets we needed to worry about had made their way through the entire pipeline from start to finish and we had 837 bridged BAMs. But, with my paranoia getting out of hand (and given the events so far, perhaps it was now justified), I collected the file sizes for each class of intermediate file and calculated summary statistics.

Unsurprisingly, I found an anomaly. For one class of file, BAM files that were supposed to contain all reads that binnie determined as requiring re-alignment as they fell on a bridge: a high standard deviation and rather postively skewed looking set of quartiles. Looking at the files in question, 387 had a size of 177 bytes. Opening just one with samtools view -h drew a deep but unexpected sigh:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

@SQ SN:MT LN:16569 @SQ SN:NC_007605 LN:171823 @SQ SN:hs37d5 LN:35477943 @PG ID:bwa PN:bwa VN:0.5.9-r16 |

Empty other than a modest header. Damn. Damn damn damn. I went for a walk.

The LSF records didn’t reach far back enough to let me find out how this might have happened, September 2014 was millions of jobs ago. The important thing is that this problem didn’t seem to be happening to newer jobs that had generated this particular class of file more recently.

Why was this still causing trouble now? Remember: File Creation is Success!

The solution was to nuke these “has_177” files and let the Makefile take careof the rest.

The Class of 2014

Once that was complete, we had a healthier looking set of 837 lanelets and your average “bridged” BAM looked bigger too, which is good news. Ultra paranoid, despite the results now passing quickcheck, I decided to regenerate a small subset of the 450 non-177 lanelets from scratch and compare the size and md5 of the resulting files to the originals.

They were different.

The culprit this time? Indexes built by bwa that were generated in 2014 were much smaller than their 2015 counterparts. In a bid to not keep repeating the past, I nuked any intermediate file that was not from that week and let the Makefile regenerate the gaps and final outputs.

All now seemed well.

Final Checks

Not content with finally reaching this point, I tried to rigorously prove the data was ready for the sample improvement step via vr-pipe:

quickcheck

Ensure the EOF block was present and intact.bsub -e

Checked that none of the submissions had actually reported an error to LSF during execution.bsub -d UNKN

Ensured that submissions did not spend any time during execution in an “UNKNOWN” state, an indicator of the job stalling and likely producing bad output.samtools view -c

Used the counting argument ofsamtools viewto confirm the number of reads in the final bridged BAM matched the number of reads in the input lanelet. Usingsamtools viewto count records in the entire file will also catch issues with truncation or corruption (albeit in a time consuming fashion).gzip -tf

Ensure the compression of each block in the BAM was correct.

Now equipped with 870 lanelets that passed these checks, it was time to attempt BAM improvement.

tl;dr

- Finally completed the

bridgebuildingprocess that made this project impossible last year. - When files are huge, it is probably faster to simply regenerate data that is suspected broken, than to diagnose and triage what may or may not be invalid.

- LSF is almost as bad as Sun Grid Engine.

samtools sortclobbers temporary files if “misusing”-T.- Brunel translation writes beyond

transand mangleslinepointer